A major shift is happening in the global economy as manufacturers move their operations out of China. Once seen as the world’s most efficient and cost-effective factory, China is now facing a serious exodus. For companies large and small, the decision to relocate is no longer just about cost. It’s about risk, reliability, and the future of doing business in a rapidly changing world. This manufacturing migration is already reshaping global supply chains, and the trend shows no signs of slowing down.

Why Manufacturers Are Leaving China

The reasons companies are pulling out of China are numerous. While some of the movement began years ago, recent events have made the situation more urgent. One of the biggest driving forces is the re-election of U.S. President Donald Trump and the return of his aggressive trade policy. In his second term, Trump has expanded his use of tariffs, imposing a 104 percent levy on Chinese goods. China responded by slapping 84 percent tariffs on U.S. imports.

This back-and-forth has had a chilling effect on trade between the two countries. According to James Gorrie, a writer for The Epoch Times, this is déjà vu for China, but “only much worse.” He explains that “Trump’s second term of tariff mania” is changing the entire structure of global trade. In fact, many companies are moving not only to avoid tariffs but also to escape the unpredictability of China’s government policies and geopolitical actions.

The pandemic also played a major role. China’s severe COVID-19 lockdowns caused massive disruptions to supply chains, exposing the danger of relying too heavily on one country. Gorrie notes that “thousands, if not millions, of China’s manufacturing customers saw extended disruptions in their businesses and suffered significant losses.” For many companies, the lockdowns were a wake-up call that pushed them to diversify their manufacturing bases.

Another major issue is China’s rising labor costs. The country’s workforce is aging, and wages are no longer as competitive as they once were. The Chinese economy has also shifted its focus toward domestic consumption rather than export manufacturing. This makes it harder for foreign companies to compete on cost and efficiency.

Political and military tensions are making things worse. China’s aggressive actions in the Asia-Pacific region, especially near Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Japan, have raised alarm among global businesses. These tensions have created concerns that the region could become a conflict zone. As Gorrie explains, “many of China’s customers’ concerns are driven largely by CCP aggression against neighboring countries.”

European companies are just as wary. In a 2024 survey, 44 percent of European Union Chamber of Commerce members said they expect declining profits in China and expressed frustration over restricted market access. And that was before Trump’s new tariffs began in 2025.

How Many Companies Are Leaving?

The numbers tell a clear story. According to a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, around 30 percent of U.S. companies are either actively moving their supply chains out of China or seriously considering it. That is more than double the number from 2020. Back then, the main cause was China’s strict COVID policies. Now, a wider range of issues are pushing companies to leave.

Export-focused companies have been hit the hardest. These are firms that manufacture goods in China not for the Chinese market but for global markets, especially the United States. “Export manufacturers are taking tariff bullets,” wrote Gorrie. American businesses have also faced unofficial boycotts and strict inspections from the Chinese government, which has only increased their costs and risks.

Who Is Most Exposed?

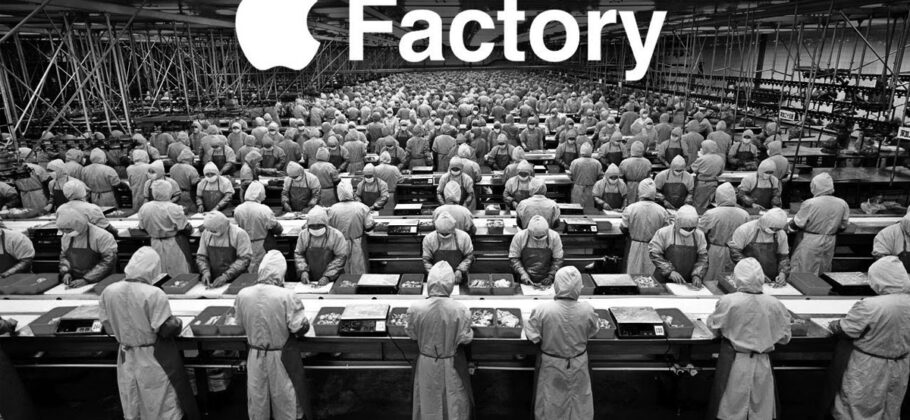

Some of the biggest names in American technology and manufacturing are deeply exposed to the risks of staying in China. Apple, for example, produces around 70 percent of its products there. Bank of America estimates that the company could see a $20 billion increase in the cost of goods sold due to tariffs and supply chain issues.

Dell and HP are also in a difficult position. Dell makes about 40 percent of its products in China, while HP produces 30 percent there. These companies, according to Bank of America analyst Wamsi Mohan, “are expected to fare the worst given high exposure to China.” Mohan explained that these firms have some tools to soften the blow — such as adjusting pricing or shifting production — but their heavy reliance on China remains a problem.

Other companies with large Chinese supply chains include Logitech, Juniper Networks, Western Digital, and Corning. These firms now face increased scrutiny from both the U.S. and Chinese governments, as well as rising costs and shipping delays.

Where Are Manufacturers Going?

As companies leave China, they are not all going to the same place. Many are spreading their operations across multiple countries to reduce risk and avoid future disruptions. This strategy is often called “China Plus One,” meaning that a company will keep some production in China but add another country to diversify.

Vietnam is one of the top destinations. It offers low labor costs, a skilled workforce, and good infrastructure. Because it borders China, it allows manufacturers to continue sourcing parts from their existing suppliers. Vietnam is also politically stable and has made major investments in transportation and energy systems. According to Gorrie, “Vietnam has seen a significant influx of investment over the last five years, and this is only expected to increase.”

India is another popular option, especially for companies that already have a presence there. Apple, for example, has begun producing more iPhones in India and plans to move up to 25 percent of its production there by 2028. But India faces challenges, including higher costs, weaker infrastructure, and a slower approval process. “Even if India were to benefit from this in the short-term,” said Jayant Dasgupta, former ambassador to the World Trade Organization, “that can only be done if we have China’s economies of scale.”

Mexico is also attracting manufacturers, especially those that want to be closer to the U.S. market. Under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), many goods made in Mexico can enter the U.S. without tariffs. Companies like Dell and HP already produce some of their products in Mexico and may expand those operations.

Other Southeast Asian countries like Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Malaysia are also part of this new manufacturing map. Thailand, for example, is seen as a strong choice for companies that want to add value to their products and serve both Asian and global markets. It offers skilled labor, deep industry clusters, and a strategic location.

Will This Trend Continue?

All signs suggest that the migration out of China is not temporary. As Gorrie put it, “China’s golden days of being the world’s factory are fading fast.” The reasons behind the shift — rising costs, political risk, and the need for supply chain diversity — are not likely to go away any time soon.

Even if trade tensions between the U.S. and China calm down, companies are unlikely to return in large numbers. The damage has already been done. Businesses now see the risks of being too dependent on a single country, especially one that can shut down its economy overnight or become the center of a geopolitical crisis.

China is trying to respond by building closer economic ties with countries like Argentina, Brazil, and Russia. But its biggest hope is still the European Union, which remains cautious about taking on more economic risk.

In the end, the global supply chain is being rebuilt. It is becoming more regional, more diversified, and more resistant to disruption. As companies search for new locations, they are not just looking for low costs. They are looking for reliability, political stability, and the freedom to do business without interference.

As one analyst said, “The trade war may drive companies toward new market opportunities they may have otherwise overlooked.” For the first time in decades, the question is no longer just how much can be made in China — but where in the world it makes the most sense to build the future.