The heart of Arkansas’s lithium story lies beneath the pine and bayou country of the Smackover Formation, a saltwater brine aquifer that arcs across southern Arkansas into Louisiana and Texas. Lafayette County sits right on top of it, with test wells tucked behind timber stands and cattle fields near Lewisville and Stamps. In 2024, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated up to 19 million tons of lithium dissolved in brines under four southern Arkansas counties, enough to replace U.S. imports and more, according to survey hydrologist Katherine Knierim. Companies have been scouting here since at least 2017, often quietly, and by late 2023 and 2024 they began showing their hand with leases, test wells, and public office openings along Route 82.

Who Is Moving In

Big names are staking claims. Exxon bought mineral rights to about 120,000 acres across Lafayette and Columbia counties and drilled its first lithium well with production targeted for 2027. Standard Lithium, partnered with Norway’s Equinor and backed by Koch, has run a five-year demonstration at a Lanxess bromine plant in El Dorado, processing more than 30 million gallons to prove its direct lithium extraction process, and is planning a central processing facility in Lafayette County. The company received a $225 million Department of Energy grant and says phase one will directly employ about 100 people. Tetra Technologies, a longtime bromine player, controls about 40,000 acres of brine rights and is developing the Evergreen Brine Unit south of Stamps with an Exxon affiliate, as well as the Reynolds Brine Unit with Smackover Lithium. Chevron has announced large acreage positions in northeast Texas and southwest Arkansas. Albemarle, already a bromine heavyweight in the region, is working on lithium extraction as well.

How Big Could the Boom Be

Projections are head turning. Standard Lithium estimates its Lafayette County facility could produce 22,500 tons of battery-grade lithium a year by 2028. Broader Smackover output could eventually reach 100,000 tons a year. State leaders talk about Arkansas becoming the nation’s leading source of lithium. One optimistic figure, cited in a local briefing, put the long-run economic potential at $19.1 trillion over 20 years, although prices are volatile and global market dynamics are rough. Lithium sold for as much as $82,000 per metric ton in 2022 and fell near $8,300 by 2025, a reminder that even white gold is a commodity.

What It Could Mean on the Ground

For places like Lewisville, the county seat with one unplugged traffic light and a main street of boarded storefronts, lithium feels like a last, best chance. County Judge Valarie Clark calls her hometown a little flower about to bloom. The pitch is straightforward. Construction brings hundreds of jobs. A modern plant, if it stays, anchors a tax base, attracts suppliers, and keeps young people from leaving. South Arkansas College has already built a 16-week pre-employment program that helped a local worker jump from custodial work to a lab tech role with higher pay. Companies talk about training partnerships with the University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana and pipelines for high school graduates.

Yet even boosters know the math. Industrial construction can employ 300, 500, even 1,000 workers for a time. Ongoing operations can be lean, often near 100 jobs per site, many of them specialized. Local newspaper publisher Tommy Goodwin worries that a chunk of those jobs will require skills beyond what the county can supply, bringing in workers from elsewhere. Housing, food, and services are thin. There are Dollar Generals but few restaurants. The only motel was shuttered for a decade and has only recently reopened. Clark is already concerned about where incoming crews will live and eat, and how the county can capture more than wear and tear on roads.

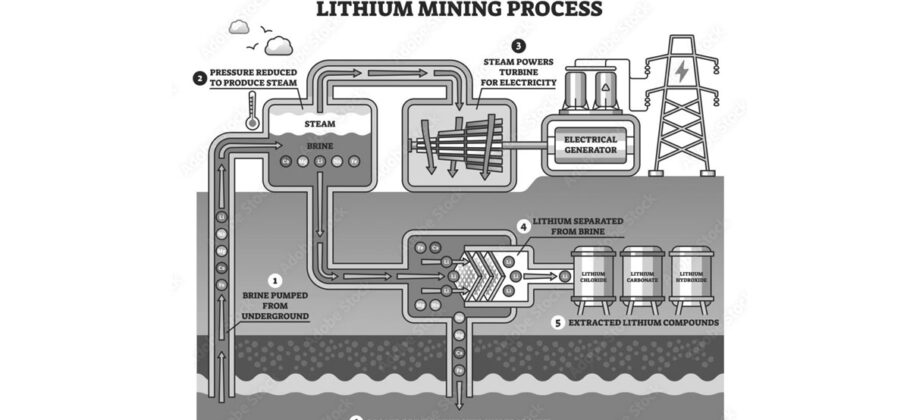

Companies here do not plan open pits or evaporation ponds. They are betting on direct lithium extraction, often called DLE. In this process, operators pump brine from the Smackover, strip out lithium using selective materials, and return the brine underground. Advocates point to research suggesting lower land and water impacts than hard-rock mining or evaporation. But nothing is impact free. DLE still consumes freshwater and produces waste streams that include solids. Local memories of salted soils and leaking brine lines from the oil era run deep, and residents want strong oversight of pipelines, disposal, and water use from the outset.

A Region with Long Memory

The last resource rush made and unmade fortunes here. In the 1920s, oil fields around the Smackover produced tens of millions of barrels, then declined. Towns like El Dorado and Smackover enjoyed decades of prosperity while other communities lagged and then withered as wells slowed. Buildings closed. Schools consolidated. In Lewisville, population fell to fewer than 900 and the hospital shut down. That lived history shapes today’s cautious welcome. People remember that outsiders often took the highest paid slots, that royalty checks did not flow evenly, and that when the boom ended the companies left and left problems behind.

The Boom and Bust Risk

Resource booms rise and fall on price, technology, and geopolitics. Lithium’s plunge from record highs illustrates how quickly margins can shrink. The industry argues DLE and downstream processing create more value per barrel of brine than bromine or oil once did, but that does not erase the cycle. It just changes where profits accrue. Skeptics point to Nevada, where a large lithium mine is expected to employ about 300 people once operating, after a construction surge of roughly 1,500 temporary jobs. They also point to global dynamics, including Chinese producers who can undercut prices to slow U.S. build-out. Locals see risk that Lafayette County hosts the impact of a boom while the durable gains accrue in boardrooms and distant supply chains.

How the money flows is still unsettled. Oil and gas pay severance taxes and royalties in the teens. Lithium does not yet have a severance tax in Arkansas. The state charges a modest per-barrel brine fee and has been working through royalty structures. Standard Lithium and Exxon have seen 2.5 percent royalty rates set in some cases. Industry has pushed for rates below oil and gas, arguing high processing costs. Landowner groups want more. Small landowners with heirs’ property worry they will be squeezed or picked off. City leaders want written commitments on housing, training, and infrastructure, not just ribbon cuttings and sponsorships. Exxon has pledged a $100,000 endowment for local grants, and opened community offices, but officials say they will keep pressing for long-term, enforceable benefits tied to production.

Optimists See a Once-in-a-Century Shot

Optimists in Lafayette County talk about reindustrialization, not a quick strike. Smackover Lithium’s feasibility work projects 45,000 tons a year for at least 20 years at one site. Tetra’s general manager, Sarah Palazzi, frames the brine not as a single-metal play but a basket that includes iodine, magnesium, and manganese. She highlights emergency power batteries and the value of having a domestic supply chain that anchors careers at home. State Rep. Matt Duffield, a fourth-generation aggregates guy who has moved from the ring to the legislature, says the opportunity is big enough to energize the entire state and argues that the right policies can translate geology into middle-class lives. Local educators already have their first success stories. City council member Chantell Dunbar-Jones believes the positives outweigh the negatives, if companies are serious about training and community partnerships. Mayor Ethan Dunbar imagines a path where lithium plants play the steady role that bromine has played in nearby Magnolia, providing decent salaries, retirements, and a reason to stay.

Skeptics Warn About the Fine Print

Skeptics counter with specifics. Construction waves fade, operations stay lean, and specialized roles go to non-locals. Freshwater consumption and waste disposal will add up across many wells and facilities. Pipelines can leak. Oversight falls on thinly staffed state offices that depend on citizen reporting. With no severance tax and low royalties, counties may not capture enough to fix roads, expand housing, and build water systems fast enough to keep up. Some residents of historically Black communities fear a repeat of the oil era, when the dirtiest work and the smallest checks landed on their side of the tracks. Retired teacher Virginia Henry puts it bluntly. Outsiders will ease in, do the work, and ease out. Then locals will be left with soils that will not grow, contaminated water, and asthma. Newspaper man Tommy Goodwin worries the big promises will not translate to sustained, broad-based jobs, and that the plants will run with small staffs, many from outside the county.

County Judge Valarie Clark and her predecessor, Danny Ormand, have learned that everything that glitters is not gold. They want clear timelines, public briefings, and specifics on housing, restaurants, and temporary worker camps. They are pushing for training pipelines that start in high school, so Lafayette County kids can move into operators’ roles, lab techs, and maintenance jobs. They want companies to fund utility upgrades, support schools, and help local entrepreneurs fill service gaps, not just import franchise chains. They want the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission to set fair royalties and for lawmakers to consider a severance mechanism that sends a steady stream to host communities. And they want emergency plans for leaks, road funds tied to truck traffic, and reporting systems accessible to residents rather than buried in paperwork.

There is the day in 2019 when Danny Ormand heard on television that the nation’s largest lithium deposit sat under his county and thought, what are they talking about. There is the new Smackover Lithium office at the Route 82 and Route 29 intersection, a tangible sign in a row of quiet storefronts. There is Tetra’s 140-foot titanium tower move planned for the Evergreen site, a parade of sorts on rural roads. There is the Rotary lunch in the high school gym, where the reporter who covers everything from circuit court to home football games grapples with a county whose school enrollment just dropped again. And there is a city council member finishing a turkey sandwich at the lone thriving lunch counter, hopeful that this time the companies will put real commitments in writing and leave the town a little better off than they found it.

There is real lithium under Lafayette County, proven technology to pull it out of brine, and serious companies putting money on the table. There is also a century of boom-bust muscle memory, scarce housing, thin public services, and open questions about who captures the upside. The path to a lasting win looks less like a rush and more like a compact. Train locals first. Put community benefits in contracts. Price the resource so that counties share gains when the market is strong. Plan for water, waste, roads, and housing before the first big crew arrives. If Arkansas writes that playbook and sticks to it, Lewisville’s unplugged traffic light could blink green again. If not, the region may hear once more the sound it knows too well, trucks downshifting on Route 82 as the next boom rolls on.