Deflation, which is a general fall in prices, has become one of the biggest worries for central banks around the world. Headlines warn of “deflation threats” and policymakers rush to prevent inflation from slipping anywhere near zero. Yet several economists argue that this fear is often exaggerated, and that in some situations falling prices can even be good for ordinary people.

Looking at recent developments in China, India, and other Asian countries, as well as lessons from Japan, Europe, and the United States, one theme stands out. Deflation is not always the same thing. The causes and the context matter. In some cases it can signal serious economic trouble. In others, it may simply reflect cheaper energy, technological progress, or intense competition that helps consumers.

This article explains what deflation is, why it is feared, how different countries are experiencing it, and why some experts argue that central banks should focus less on panic and more on the underlying reality.

What is Deflation?

Deflation is a sustained fall in the general level of prices. That means the inflation rate is below zero and stays there, not just for a month or two, but for a meaningful period of time. This is different from disinflation, which is when prices are still rising but at a slower pace.

Economist Mark Thoma draws this distinction clearly. He notes that deflation is “an actual fall in prices” while disinflation is “just the inflation rate getting lower.” That difference matters because people and policymakers often confuse the two. When inflation drops from 6 percent to 2 percent, it may feel like prices are easing, but prices are still going up, just more slowly. That is not deflation.

Jeffrey Tucker also criticizes the sloppy language around deflation. Writing about India, he points out that when central bankers complain about “low inflation” at 2 to 3 percent, they are not describing actual falling prices. They are describing a lower rate of inflation and treating it like a crisis.

The Historical Root Of Deflation Fear

The deep fear of deflation did not appear out of nowhere. It has strong roots in the Great Depression of the 1930s. During that period, prices fell sharply. In some years, they dropped by 20 to 30 percent. This painful experience left a scar on the economic profession and created what Tucker calls an “entrenched phobia of deflation.”

Tucker argues that policymakers in the 1930s got cause and effect backwards. They blamed deflation for the economic collapse and decided that rising prices were the cure. As he describes it, “the purchasing power of the dollar actually gained 66 percent between 1920 and 1933” after an earlier decline. For ordinary people, this meant that money in a mattress became more valuable over time, something he calls “absolutely glorious for the public.”

However, Herbert Hoover and later Franklin Roosevelt were persuaded by experts that falling prices were the main problem. Hoover tried to “repump the economy” by raising wages, setting price floors, and using the Federal Reserve to reflate. Tucker describes Hoover as a “huge interventionist” who effectively ran a test version of the New Deal before Roosevelt.

When Roosevelt came into office, he went even further. According to Tucker, Roosevelt “devalued the money by closing the banks and then forcibly grabbed gold from the people.” He changed the value of the dollar by executive order, interfered with labor markets, and heavily subsidized industry. Tucker’s view is that these efforts took away the one “silver lining” of the early 1930s, the lower prices that “made products more affordable and rewarded thrift.”

This historical story became the foundation of modern central bank doctrine. Deflation was labeled the villain and inflation, at least a small amount of it, was seen as a necessary medicine. Even today, Tucker argues, “elites fear deflation far more than inflation,” despite the large loss of purchasing power that inflation has already caused.

How Deflation Can Damage An Economy

The classic case against deflation is set out by Mark Thoma. He lists three main reasons to fear it, especially when it is severe and persistent.

First, expectations. If people think prices will be lower in the future, they wait to buy. Thoma gives a simple example. If you are planning to buy a car and expect the price to be “a lot lower six months from now,” you will likely delay. When millions of consumers do this at the same time, current demand drops and the economy slows.

Second, debt burdens. Deflation raises real interest rates and the real value of existing debts. If prices fall while nominal debts stay fixed, borrowers must pay back money that is worth more than when they borrowed it. Thoma explains that this shift can lead to what Irving Fisher called a “debt-deflation spiral,” where falling prices and rising real debt loads reinforce each other and “the economy crashes.”

Third, sticky wages. Wages and prices do not adjust quickly. Wages in particular tend to be sticky on the way down. When prices fall but wages do not, the real cost of labor rises. Businesses may respond by cutting jobs rather than cutting wages, which raises unemployment and further reduces demand. Thoma notes that “outright deflation isn’t required” for these problems to appear. Even disinflation can create stress if debts are large and the economy is fragile.

Central banks remember both the Great Depression and Japan’s long years of low inflation and near deflation. These experiences reinforced the idea that even small dips toward zero inflation could be dangerous.

Why Some Economists Say The Fear Is Overblown

Other economists take a very different view. Daniel Gros argues that “central banks throughout the developed world have been overwhelmed by the fear of deflation” and that this fear is “unfounded.” His main point is that central banks are looking at the wrong indicators.

Instead of worrying about small changes in consumer prices, he says they should focus on nominal GDP growth, which measures the total revenue in the economy. In his words, “the GDP price index in developed countries is increasing by 1–1.5%” and nominal GDP growth is “expected to reach about 3%” in the eurozone. At the same time, long-term interest rates are even lower. That means financing conditions are actually quite favorable, not devastating.

Gros also points to Japan as “a poster child for the fear” of deflation. For decades, Japan has had gently falling or very low inflation. Yet the country has not collapsed. He notes that “unemployment has virtually disappeared” and that disposable income per person “is rising steadily.” In fact, during the so-called lost decades, Japan’s per capita income grew “as much as it did in the United States and Europe,” and the employment rate rose. That evidence suggests that mild deflation can coexist with decent growth and high employment.

Ramesh Ponnuru adds another nuance. He argues that what matters most is the cause of falling prices. If prices decline because of a “tumble” in oil prices or a jump in productivity, that is generally good. It means energy is cheaper or goods can be produced more efficiently. He says that “deflation isn’t something we should fear” in such cases. Only when falling prices reflect collapsing demand should central banks be truly alarmed.

Ponnuru also warns that focusing too much on price level changes can mislead policymakers. For example, rising oil prices in 2008 made the Federal Reserve so worried about inflation that, in his words, “it was slow to react to the financial crisis.” Now, he argues, the opposite mistake could occur if central banks overreact to falling energy prices by loosening policy without good reason.

China’s Struggle With Real Deflation Pressures

China is one of the clearest modern examples of how deflation pressures can emerge.

Recent reports describe “chronically low inflation that is a hallmark of stagnation.” Consumer prices have dipped into negative territory and factory prices remain weak. The country is struggling with “mammoth debt, a real-estate market downturn, high levels of youth unemployment, and a broad economic slowdown.”

At the same time, investors have been shunning “riskier assets like stocks and real estate” and piling into government bonds. That shift pushed long-term interest rates to record lows. The People’s Bank of China responded by temporarily stopping its purchases of government bonds. The central bank’s move was described as an “unexpected action” aimed at tamping down a potential bond bubble.

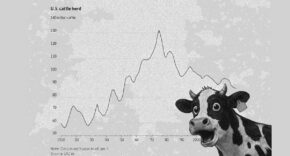

Across Asia, low-priced Chinese exports are putting downward pressure on prices. One analysis describes a “low-price offensive” driven by China’s oversupply. The Chinese government has subsidized industries such as steel, autos, and petrochemicals. With weak domestic demand, these excess goods are exported at low prices. As a result, China’s export volume has increased, but its export price index has fallen by about 15 percent. The country’s trade surplus with developing Asian nations has doubled.

This flood of cheap goods is pulling down prices in neighboring countries. The Economist is quoted saying that “the ripple effect has hit the Asian economy the hardest.” For example, car prices in Thailand have fallen by 6 percent over the past year because of Chinese competition.

In addition, China’s own inflation rate turned negative for several months, and the official People’s Daily has admitted that “some issues in economic operations” such as supply gluts are preventing balance between supply and demand. All these signs point to a mix of weak demand, excessive debt, and oversupply. In this type of environment, deflation pressures can be a real warning sign of deeper structural problems.

India’s “Low Inflation Problem”

India presents a different kind of case. After years of high inflation, India has finally brought price growth down to roughly 2 to 3 percent. Jeffrey Tucker estimates that the currency has lost around 30 percent of its value over five years, which means the damage from inflation has already been done. Now that inflation has slowed, some commentators are sounding alarms about a “low inflation problem.”

Bloomberg and Economic Times are cited promoting the idea that “the pace of price increases is worryingly low.” One headline asks “What India can do about its low inflation problem,” even though prices are still rising. Tucker notes that this is not deflation “not even close.” It is simply lower inflation.

His criticism is that the public language around inflation and deflation has become confusing. Falling inflation is treated as if prices were falling. Central banks, he argues, are conditioned to believe that anything below their target is dangerous, even after a period of runaway inflation that hurt savers and consumers.

India’s experience shows how fear of deflation can appear even when the actual situation does not meet the definition. It also shows how different the policy response might be in a country that still has strong growth prospects and a younger population, compared with a country like China that is battling heavy debt and weak demand.

Other Asian Economies On The Edge

Beyond China and India, many Asian economies are dealing with very low inflation and fears of deflation.

China and Thailand have recorded negative inflation rates for several months. Thailand’s inflation was projected at between negative 0.7 and negative 0.2 percent in recent quarters. The Thai government insists that “while inflation is low, there are no widespread signs of deflation,” but the concern is clear. The Bank of Thailand has even cut its benchmark interest rate to 1.5 percent to avoid an economic downturn.

Other countries, like Malaysia and South Korea, have seen inflation fall to the low 1 percent range. The Asian Development Bank reports that inflation in most Asian countries “has fallen below central bank targets.” The average consumer price increase for the ten largest Asian economies, excluding Japan and high-inflation Bangladesh, is only about 1.3 percent.

Several factors are working together. Low-priced Chinese exports are one. Falling oil and food prices are another. OPEC has increased drilling and global wheat production has risen as the Russia Ukraine war eased. Chinese pork oversupply has also pushed down food inflation. The result is that average food price inflation in major Asian economies fell from around 5 percent to about 1 percent.

There is also a trade angle. The Asian Development Bank warns that if U.S. China trade tensions rise again, inflation in Asian countries excluding China could “cumulatively decline by 1.2 percentage points.” Goods that cannot reach the U.S. market because of tariffs may flood into Asian markets instead, intensifying competition and lowering prices further.

South Korea stands somewhat apart. Its inflation rate has hovered around 2 percent, near the Bank of Korea’s target. Governor Lee Chang yong has said that “current inflation is stable at 2%” and has pointed to “falling prices of Chinese imports and weak domestic demand” as reasons for slower price growth. Institutions like the Korea Development Institute and the Asian Development Bank expect inflation there to remain close to target, not plunge into deep deflation.

These varied experiences show that Asia is not facing one simple deflation story. Some economies are close to or below zero inflation, others are at target, and the drivers range from Chinese oversupply to global commodity shifts.

How Europe, The United States, And Japan Fit In

In Europe and the United States, deflation fears have also been strong, but the outcomes have not matched the nightmare scenarios.

Daniel Gros notes that in the eurozone, the GDP deflator is rising at about 1.2 percent, and nominal GDP growth is around 3 percent. Long term interest rates are even lower. That means nominal growth exceeds the interest rate, which he describes as “financing conditions as favorable as they were at the peak of the credit boom in 2007.”

In the United States, Ramesh Ponnuru points out that falling oil prices have sparked warnings about deflation, yet the underlying economy remains solid. Most Americans, he notes, are “happy that the price of oil has tumbled.” The danger is that central bankers misread these good price declines and loosen policy too much, or that they become obsessed with protecting a specific inflation number.

Japan remains the classic example of how an economy can function under mild deflation or near zero inflation for decades without collapsing. With low unemployment, rising employment rates, and steady gains in disposable income, Japan challenges the idea that deflation always means stagnation.

Different Situations, Different Effects

Taken together, these examples show that deflation is not a single, simple threat. In some contexts, like China’s mix of debt, oversupply, and weak domestic demand, falling prices can signal deeper trouble and create real risks of a painful adjustment. In others, such as Japan’s long period of mild deflation or the recent drop in oil prices that benefit consumers, deflation or near deflation can be compatible with growth and rising living standards.

The key questions are:

• Are prices falling because demand is collapsing, or because productivity and supply are improving

• Are debts so large that even small price declines threaten a debt-deflation spiral

• Are wages flexible enough, or will sticky wages create large employment problems

• Are central banks reacting calmly to the data, or panicking based on outdated fears

Jeffrey Tucker believes that the “myth” of deflation as an automatic disaster still dominates elite thinking. Daniel Gros argues that central banks should “overcome their irrational fear” and stop trying desperately to stimulate demand in situations where financing conditions are already very favorable. Ramesh Ponnuru insists that we must always ask what is causing prices to move before deciding how to respond.

The world’s experience suggests a simple conclusion. Deflation in a heavily indebted, slowing economy can be harmful and must be watched carefully. But mild deflation or very low inflation caused by cheaper energy, oversupply, or technological progress is not necessarily a crisis. Different situations will have different effects, and treating every fall in inflation as a disaster can be just as dangerous as ignoring the real risks when they do appear.