A Personal Move That Reflects a National Shift

When real-estate titan Donald Bren decided to unload the last of his downtown San Diego office towers, many observers saw it as more than just a business decision by a 93-year-old tycoon. His choice to walk away from a half-dozen buildings over two years captured a broader, unsettling trend that has reshaped American cities since the pandemic. Companies no longer need the massive downtown offices they once relied on, and the market has struggled to adapt.

Bren’s final sale, a deeply discounted deal for One America Plaza, brought this shift into sharp focus. Norman Miller, a real-estate professor emeritus at the University of San Diego, called the decision “a really heartbreaking signal to other owners in the central business district.” He added that Bren’s exit sends a message that the problems downtown faces could last for years.

But the bigger story is not Bren himself. It is the reality of a national office market that is still being hollowed out five years after the pandemic began.

Why Office Demand Collapsed

When Covid hit, millions of workers were suddenly working from home. What was expected to be temporary turned into a permanent change. Companies discovered that they could operate with far less space, or with cheaper space, or with a mix of smaller offices in different locations. As a result, large corporate footprints started shrinking everywhere.

From 2020 to 2024, tenants handed back more than 180 million square feet of office space. Entire downtown districts lost tenants that had anchored towers for decades. Many firms simply let leases expire. Others subleased floors they no longer needed. Still others kept only small portions of the space they once occupied.

U.S. Bank’s downsizing is a clear example. The bank is giving up most of its space in the Seattle U.S. Bank Center, cutting its footprint from seven floors to less than one. A bank representative explained that the company is constantly seeking ways “to better serve employee, client and business needs,” and that means less space than before the pandemic. In Portland, U.S. Bank walked away from five floors in the city’s iconic U.S. Bancorp Tower, a move so significant it encouraged UBS to put the entire property on the market.

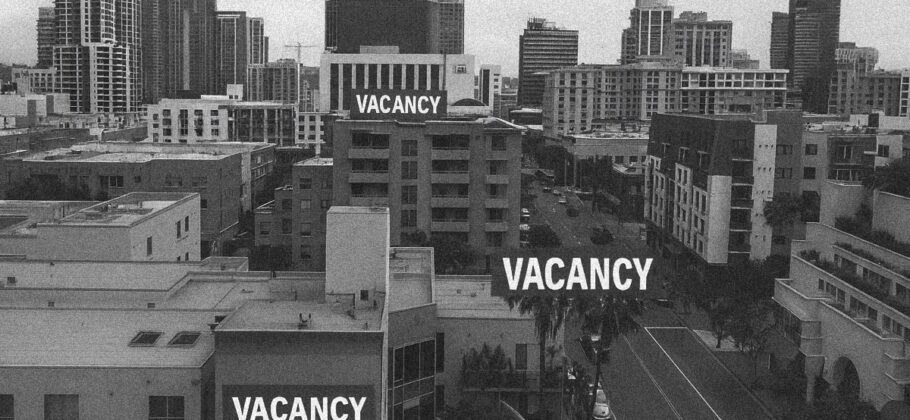

These decisions are not isolated. Tenants across the country are taking similar steps. Lease sizes have fallen about 20 percent from pre-pandemic levels. The national vacancy rate has climbed above 14 percent, the highest ever recorded.

Bren Signals a Trend

This is what makes Bren’s retreat from San Diego so symbolic. He is known for making big decisions based on long-term trends, not short-term swings. His history includes acquiring 93,000 acres of Orange County land in 1977, a move widely considered one of the greatest real-estate purchases of the century. He tightened expenses and reduced debt in the 1980s, long before most developers realized the early 1990s crash was coming. When he later doubled down on coastal holdings, those markets went on long upcycles.

So, when someone with that kind of track record steps back from downtown office towers, it raises alarms. Dylan Burzinski of Green Street put it bluntly when he said, “I would not say the San Diegos of the world fit that bill.” He meant that investors are concentrating their money only in the strongest markets, and cities like San Diego no longer meet that standard.

Bren is hardly the only one making this call. Many institutional investors now prefer suburban areas or high-growth pockets like La Jolla and University Town Center. Downtown San Diego’s vacancy rate hit 35.6 percent in the third quarter, more than double those of the city’s healthier submarkets.

The Long-Tail Effects of Remote Work

Return-to-office policies from companies like Amazon, Starbucks and Walmart have lifted demand in some places, but the recovery is uneven. Many employers discovered that hybrid work saves money and increases worker satisfaction, so they see no need to return to the old model of filling an entire skyscraper.

Matthew Harrison, a business law expert in Arizona, noted that landlords now face pressure to redesign buildings, cut prices or add amenities such as natural light and outdoor spaces. He wrote that landlords are trying to avoid a wave of vacancies that could create cash flow problems.

Cushman and Wakefield says downsizing may have peaked, meaning the worst of the reductions could be over. Their 2025 survey found that only 32 percent of companies plan further cuts, and lease sizes have grown 13 percent over two years. Rob Hall, a head of portfolio management at the firm, said some capital spending decisions are being delayed but not abandoned. He believes organizations will continue following their long-term strategies once economic uncertainties settle.

Still, vacancy remains high in many cities, and it may take years to find equilibrium. Office utilization globally is stabilizing between 51 percent and 60 percent, well below pre-pandemic norms.

New Buyers and New Approaches

While big players like Irvine are leaving, smaller entrepreneurial investors are stepping in. Daniel Negari’s firm XYZ purchased two of the buildings Irvine sold and is spending money to reposition them with conference centers, flexible floor plans and amenities aimed at startups or small companies looking for bargain rates. CBRE executive Matt Carlson said, “They are incredibly entrepreneurial,” suggesting that some buyers see opportunity where institutional investors see risk.

These new owners are willing to take risks because they bought the buildings at steep discounts. They believe that, with creativity and patience, they can rebuild demand over time.

San Diego has strengths that separate it from other struggling cities. Tourism, biotech and residential development remain strong. New cultural attractions like a Navy SEAL museum and the arrival of TED’s flagship conference keep the downtown area relevant.

But none of that solves the core problem facing the office market. As Miller said, “It tells you that this is not just a cycle. This is expected to be a long-term issue.”

Across the nation, city leaders, landlords and employers are grappling with this new reality. How much office space does the modern workforce need? How expensive should that space be? Should companies prioritize quality over quantity? And what should cities do with towers that no longer serve their original purpose?

Bren’s decision to leave is not the story of one billionaire making a personal financial choice. It is the story of an entire era ending. The office footprint that once defined downtown America has shrunk, and it may never fully return.

Whether cities adapt with new ideas or struggle under the weight of empty towers may be one of the most important urban challenges of the coming decade.