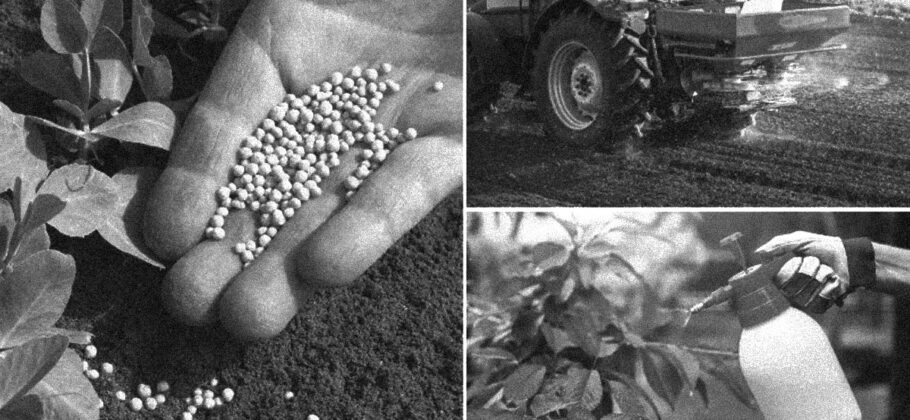

Fertilizer is one of the most essential tools in modern agriculture. Without it, crop yields fall. With it, costs rise. Now farmers across America are caught in a painful squeeze, as fertilizer prices soar while crop prices remain stubbornly low.

When even a fertilizer salesman is telling farmers not to buy, it sends a powerful warning.

A Warning From Inside the Industry

John Leach, a third generation independent fertilizer dealer in North Carolina, recently delivered a stark message. “It’s not looking good for farming this year,” he said.

Leach owns two fertilizer plants and represents a shrinking number of non corporate operators. Independent input sellers, like independent farmers, are disappearing as consolidation spreads through agriculture.

When asked why he is urging caution, the answer is simple. Nearly every input used to manufacture granular fertilizer has increased in price. Urea has jumped roughly $100 per ton in just over a month. Phosphorus now sits above $700 per ton. Even sulfur, once one of the cheapest components, is climbing sharply.

Granular fertilizer remains the most widely used form because it is easy to apply at scale. But with commodity prices for corn and soybeans too low to absorb rising input costs, farmers are being squeezed from both sides.

The Gap Between Costs and Income

New USDA data show just how severe the squeeze has become. By October 2025, the prices paid index had climbed to 154.6 while the prices received index had fallen to 120.5. That means production costs were more than 50 percent higher than in 2011 levels, while prices farmers received were only about 21 percent higher.

The gap reached 34.1 index points, “the widest spread in the data going back at least a decade.”

“These indexes don’t measure profits directly, but they offer a clear signal of rising financial pressure on farm operations heading into the next season,” reported Investigate Midwest.

Farmers feel it every day. Kentucky farmer Caleb Ragland told senators, “Farmers are paying more than ever to grow their crops. In just five years, seed prices have increased by 18%, fertilizer by 37%, pesticides by 25%, machinery by 23% and interest expense by 37%.”

With grain futures down for multiple years and record yields pressing prices lower, margins are shrinking or disappearing entirely.

As fertilizer executive Corey Rosenbusch put it, “Right now, it’s a perfect storm. Commodity prices are low, and input costs keep going up and up.”

Why Fertilizer Is So Expensive

The reasons are complex and global.

James Hoorman of Hoorman Soil Health Services points to supply disruptions from the Russia Ukraine war, China cutting back on exports, high tariff costs, port congestion, and high energy prices.

“High volatile fertilizer prices will be a major concern this next year,” Hoorman wrote.

Russia and Belarus export significant nitrogen fertilizer, and the war has reduced shipments. China, a major exporter of phosphorus based fertilizer, has cut back exports. High tariffs on imports from Canada, China, Morocco, and Russia add further cost.

Natural gas, a major ingredient in nitrogen fertilizer, has also risen due to increased exports overseas. That drives nitrogen fertilizer prices higher in the United States.

Josh Linville of StoneX warns that nitrogen prices are “unlikely to drop significantly,” noting China is restricting urea exports and European production is operating at only 75 percent due to high gas costs.

Phosphate exports from China are being cut in half this year. “The world doesn’t have anyone ready to fill that gap,” Linville said.

Potash is heavily dependent on imports. The United States mines only about 3 percent of its own potassium fertilizer. Canada dominates global exports, followed by Belarus and Russia.

While the U.S. only imports about 25 percent of total fertilizer, it depends heavily on foreign sources for certain key nutrients. That global dependency amplifies volatility.

Monopoly, Oligopoly, or Market Forces

Some farmers argue that global events are only part of the story. They believe consolidation has reduced competition and driven prices higher.

Sen. Chuck Grassley warned that “over the last 20 years, a few big companies have bought up many of the smaller seed and chemical businesses.” Because products and digital systems are tied together, “it’s hard for farmers to switch to a different brand.”

Farmer Noah Coppess testified that fertilizer pricing has become “very volatile, with wild swings of 25% to 50% from year to year.”

Mark Mueller, an Iowa farmer, said, “The bottom line is that we don’t have many places to get our inputs from.” He noted that many retailers ultimately source from the same few suppliers.

Josh Linville agrees the market is not technically a monopoly, but he calls it “definitely an oligopoly.” For nitrogen, “three players control the vast majority of production.” For phosphate, there is one main producer. For potash, the United States is highly dependent on imports.

Fewer suppliers mean tighter supply chains. When global shocks occur, prices react quickly and often sharply.

Still, industry leaders insist geopolitics is the primary driver. Rosenbusch says, “These are global supply and demand pressures. When geopolitics dominate, prices react worldwide.”

What Are Farmers Supposed to Do

With little short term relief in sight, farmers are left with difficult choices.

Leach is urging growers to avoid “blanket rate” fertilizer applications. Instead, he recommends soil sampling to determine which nutrients are already present and pulling back where possible.

“If the market becomes too constricted, it is ultimately the farmer who loses,” Coppess warned. On his farm, “Phosphate fertilizer has become a bare minimum usage fertilizer because of the cost.”

Linville encourages proactive planning. “We can’t change the markets,” he said. “But volatility can also create a lot of opportunity.” He recommends placing orders in advance and buying fertilizer in layers, similar to grain marketing.

Hoorman suggests farmers consider cutting back, especially on phosphorus and potassium, which can be stored in soil organic matter.

Others are exploring building on farm fertility systems, integrating livestock, increasing compost production, and expanding cover crops. Fertility that originates on the farm is less exposed to global markets.

A National Security Question

The federal government recently added potash and phosphate to its critical minerals list. Rep. Harriet Hageman said the compounds are “indispensable agricultural inputs that keep our soil fertile, our farmers productive, and our food supply secure.”

Wyoming farmer Todd Fornstrom put it plainly. “If you don’t have plant food, your crops are gonna suffer because of it.”

He compared fertilizer price swings to “dealing with an electrical bill at the beginning of the year at $80 and at the end of the year it’s $200.”

The stakes are high. American grown food is not just a business. It is a matter of national security.

As one fertilizer dealer reflected, “The thing about farming is it’s not about money. It’s more than that. It’s about family. It’s emotional. But it needs to make money.”

Right now, for many farmers, that is the hardest part.