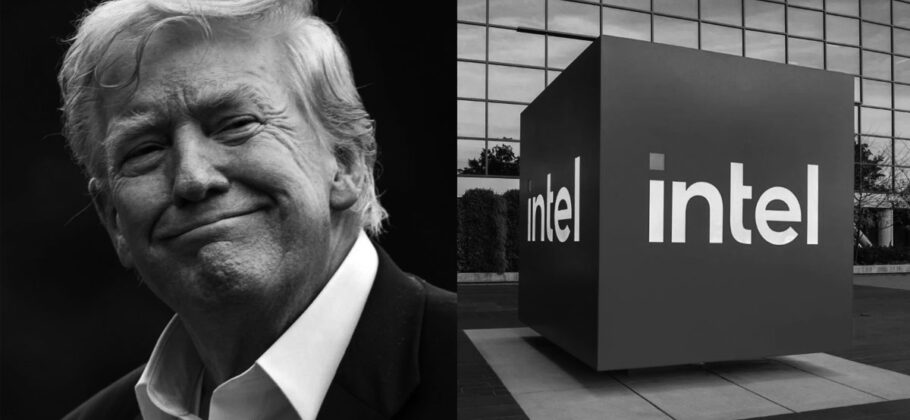

The Trump administration and Intel said the government will swap certain Chips Act grants for equity in Intel. In a separate announcement, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick detailed a direct stock purchase: the U.S. bought a 10 percent stake for 8 billion dollars, acquiring 433.3 million shares at 20 dollars each. Intel said the price was below the market rate. The government will not hold a board seat or any governance rights, and it may buy another 5 percent if Intel ever loses majority ownership of its foundry business. Intel shares rose about 6 percent on the news.

Why Washington wants in

Backers point to the 2022 Chips and Science Act, which was designed to rebuild domestic chip manufacturing after decades of offshoring. The U.S. depends heavily on Taiwan for the advanced chips that power artificial intelligence, communications, and national security systems. The authors of the Wall Street Journal op-ed explain that this dependence creates an unacceptable risk. They also stress that the law was not meant to be a money maker. As they put it, “The Chips Act wasn’t about raising revenue, and an equity share wouldn’t enhance national security.” Supporters of the stake argue that a visible, long-term commitment to Intel can signal staying power, help anchor leading-edge production at home, and reduce dangerous chokepoints in the global supply chain.

The goal is resilience. Intel is the only American company positioned to produce state-of-the-art logic chips on U.S. soil. A larger, more stable Intel foundry could give the Pentagon and key industries a domestic source for advanced chips. Intel echoed this aim. CEO Lip-Bu Tan said, “Intel is steadfastly dedicated to guaranteeing that the most cutting-edge technologies in the world are produced in the United States.” Supporters add that Intel has committed billions to new factories in Ohio, with an opening now targeted for 2030, and that strengthening this capacity would reduce reliance on foreign producers that could be disrupted by conflict or shocks.

What the Wall Street Journal authors argue against

Mike Schmidt and Todd Fisher led the Commerce Department’s Chips Program Office. Drawing on their experience, they argue that turning grants into stock is the wrong fix. In their words, “A government equity stake doesn’t solve that problem.” They say the Chips Act was designed to close the cost gap with Asia through grants, loans, and tax credits, not to create a government investor. They write that “the taxpayer’s return on these investments comes not in the form of revenue for the government but enhanced national security and supply-chain resilience.”

Schmidt and Fisher contend that Intel does not have a capital shortage. They note that “Intel has no trouble raising capital in public markets,” citing a recent 2 billion dollar investment from SoftBank as evidence. They argue that equity is costlier for Intel than grants, which could leave the company at a disadvantage against rivals that manufacture in lower-cost Asian countries while still getting direct incentives from many governments. In their view, replacing grants with equity “risks putting Intel at a cost disadvantage relative to other chip makers.”

The op-ed warns that a government shareholder brings new complications. They ask, “When policymakers set semiconductor strategy, will they be doing so as national stewards or as corporate shareholders?” If Intel announced layoffs, they argue that Washington might look as if it is profiting from job cuts. They also question how partners like Samsung and Taiwan’s TSMC will view competition with a firm partly owned by the U.S., asking, “Where does this new model of state capitalism stop?” These concerns point to conflicts of interest and the appearance of favoritism in a sector that depends on global cooperation.

The real bottleneck is customers

The authors argue that Intel’s main problem is not money. It is demand for its most advanced manufacturing nodes. They write that Intel’s foundry “lost more than 13 billion dollars last year and has almost no external customers.” They add that “Intel’s 18A process has failed to secure any meaningful external customers,” and they note the company’s own admission that it “can’t sustain its leading-edge manufacturing” without outside orders for the next node. Their proposed fix is to use public policy to push large buyers to diversify. They argue that the government should be “nudging, cajoling and creating incentives for major customers to diversify their supply chains and use Intel capacity.” The idea is to create multiple leading-edge suppliers so the global AI economy does not run on one pipeline.

Chips Act grants come with guardrails. According to Schmidt and Fisher, the awards include upside-sharing if companies reap windfalls and are tied to milestones such as “customer commitments, technology readiness, production goals and construction progress.” These steps help ensure that funds flow only when national security goals are met. They warn that the Intel transaction “appears to wipe out these milestones and instead provides cash up front,” which would weaken the government’s ability to protect the public interest.

The case in favor from industry voices

Some industry leaders say the stake is not only sensible but necessary. Former Intel CEO Craig Barrett wrote, “Yes, the USA NEEDS INTEL, as Intel is the only US company capable of providing state of the art logic manufacturing.” He has urged major customers like Nvidia and Apple to invest to secure America’s chip future. Supporters also point to market signals. The stock pop suggests investors saw the announcement as stabilizing, and President Trump argued that the shares are already worth more than the purchase price.

What exactly the U.S. is buying

At this stage, the U.S. has acquired 10 percent of Intel for 8 billion dollars, with an option to add another 5 percent if Intel no longer controls a majority of its foundry. The government will not occupy a board seat and will not hold governance rights. In parallel, officials referenced other awards for secure chips and Chips Act grants that had been authorized but not yet disbursed. One report also noted that Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company is thought to have more advanced technology than Intel, which explains why U.S. policy makers want to boost American leading-edge capacity inside the United States.

Proponents argue that the stake is a high-profile commitment that can attract customers, focus management, and give planners confidence that domestic capacity will be funded through economic cycles. They see the deal as a tool to accelerate a broader trend the op-ed authors themselves celebrate: “More than 500 billion in investment has been announced,” and all five global leaders in logic and memory are expanding on U.S. soil. Supporters believe a visible government partner can lock in that momentum.

Critics reply that equity invites political interference, blurs the line between regulator and owner, and distracts from the real task of booking large outside orders at the top nodes. They argue that grant milestones already give taxpayers leverage without making the U.S. a shareholder. In their words, “Equity in Intel isn’t resilience,” and “it is the wrong tool for the job.”

Both sides agree on the goal: reduce dangerous dependencies and rebuild American strength in advanced chips. The split is over the instrument. One camp sees ownership as a strong signal that can speed investment and secure supply. The other camp, led by the Wall Street Journal op-ed authors, says the better play is targeted grants tied to milestones and aggressive steps to win external customers. The choice will shape not only Intel’s future but the architecture of U.S. industrial policy in a sector that sits at the heart of national security.

FAM Editor: The very definition of fascism is a government that uses its industries to wield power. This is a slippery slope, one that could lead to a general control of industry by government.